A Pair of 1640’s Stays: Part 1

/In the last few years, there has been an outbreak of new books published on the subject of making historical clothing that are replicas of original items held in museums. They are different from many previously available books because they use specific garments to demonstrate how things were done in the past rather than showing generally how to get the right look for each time period.

This trend, of course, started with Janet Arnold’s Patterns Of Fashion 1, 2 and 3 published between 1972 and 1985, which were unique in their time for the attention to detail in drawing out and describing existing items of clothing under specific headings and time periods. After Janet’s death in 1998, her unpublished work was completed by Jenny Tiramani and Santina Levey and then published in 2008 as Patterns of Fashion 4. However, throughout this time, these were the only books to present actual surviving articles of clothing with scaled patterns, detailed descriptions, historical settings and paintings of similar items being worn as part of a full outfit.

1640’s Stays or Corset

Since 2009, a group of historical costumers, researchers and teachers called The School of Historical Dress having been taking Janet Arnold’s philosophy further. They have been publishing books on specific surviving examples of clothing and running courses on how to make clothes in the methods used in specific time periods and, crucially, before the invention of sewing machines!

What does this all have to do with making a pair of stays or what would now be called a corset? Simply this; when I was asked to make a corset (or pair of bodies or pair of stays, depending on your preference) I was fortunate to receive my copy of Patterns of Fashion 5 soon after. This book, published late in 2018, was researched and published by Jenny Tiramani and Luca Costigliolo in the name of Janet Arnold and it is all about bodies, stays, corsets and other “underpinnings”. All I had to do was find a pattern that looked like my client’s fairly specific request, was correct for the English Civil War Period and could be made within the budget. Simple!

Finding the right pattern

PoF 5 contains a large number of patterns for stays, bodies or corsets. However, only 9 of these are from items dated to the English Civil War period (giving that period the widest range possible!). Several of these were clearly outerwear - what we might now call a boned bodice but at the time there was no distinction between these. Since my client had been very clear in saying that hers was to be underwear to go under her existing clothes then the outerwear versions could not be considered.

As part of the information-collecting phase of the sale, the client had also specified that she wanted a corset with a long waist, i.e. the bottom of the corset would come down low. This style was more common in the later Civil War period, earlier the style had been for shorter stays. She wanted it to be front lacing and to look similar to a photo she had seen and provided.

This only left two patterns from the book. Both front lacing and both similar enough to the specification. However, one of the patterns looked very cylindrical in shape instead of curvy like the client’s photo. So now I had my pattern, page 48 Stitched Stays and Stomacher in Crimson Satin - except that my client wanted hers in brilliant white!

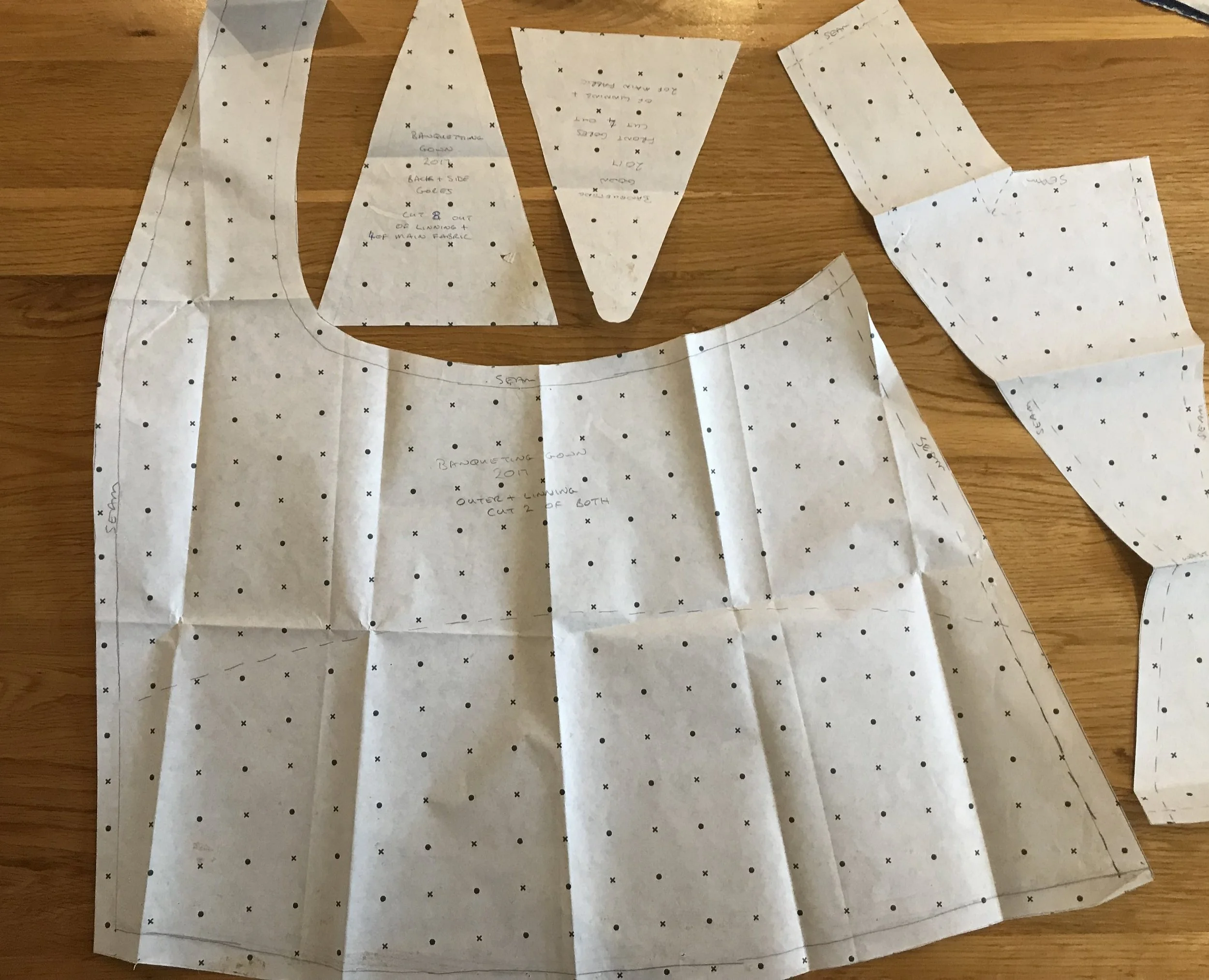

I am not going to describe scaling up the pattern here. For some information, see my previous post here on this topic. For more information contact me or look for the many sources of information on scaling up PoF patterns on the internet. Once scaled up and cut out, it looks like the picture below. They really are white but the photo looks yellow. To keep the pieces white I had to clear the workroom of all fabric other than these pieces, clean down the work surface of fabric dust and wash my hands every 30 minutes!

The stays after cutting and forming the front boning channels and eyelets

Level of Authenticity

The decision on how authentic is authentic is always hard. My preference was to try doing a copy of the original stays. However, I had to bear in mind the client’s budget and her preferences, since even fully machine stitched stays are a very major investment. So the fabric was coutil - a type of fabric not invented in the Seventeenth Century, however, it makes a fantastic fabric for stays as it is strong, does not stretch or deform and can be moulded by being stitched in certain ways.

Clearly all of the channels would be stitched by machine to save time and also look neat (my hand stitching is good but not that good yet!) but a major decision was using metal eyelets for the lacing holes. Not only was this a budget constraint but the client’s mental image of the final product included silver metal eyelets. The binding ribbon is a white gross-grain ribbon, polyester not silk I am afraid. However, I think the combination looks good.

Stays with binding strip of gross-grain ribbon

Preparing for the fitting

One of the things I have never had to do before is prepare an item for a single fitting. In the past I have had regular access to the people I have made clothes for so could keep trying things. This time, my client lives a long way away so I needed to complete enough of the stays that they could be put on, laced up and measurements made but without doing work that might need to be undone if the shape of the edges or the size of the stays needed to be changed.

The compromise that I came to was to complete all boning channels but stop the stitching short of both top and bottom edges - that way if an edge needed to be cut down, it would not cut off the end of the stitches. That decision also allows me to insert a strip of padding to help stop the boning from poking through the fabric at the ends. I decided to complete a short section of binding strip so the client could see what it would look like.

Hand stitching the side seams for the fitting - you are looking at the outside of the stays

The main thing though was to complete the front edges of the stays to there final look, including the boning and eyelets, which meant all of the adjustment had to be in the side seams. Luckily, the Patterns of Fashion 5 book has a really interesting cartoon strip of a stay maker making up a pair of stays, doing a fitting and then completing the stays. The trick he used was to make each piece up completely, leaving a lot of extra seam allowance at the side seam, and then stitch that up temporarily so that the seam was on the outside of the garment - it looks really weird to see the seams on a nearly finished corset sticking out like that. However, in the cartoon, he then does the fitting, makes any adjustments to the side seams, trims them down and then hides the raw edges under a decorative ribbon. So that is what I decided to do.

The picture shows hand stitching, with very strong thread, the side seams with their big seam allowance. You can see the shaping starting to take effect as the rounded pieces are forced gently and slowly round on top of each other by the stitching. I really think this fitting method helped me enormously as I don’t think I could have forced those edges to line up using a sewing machine. By hand it was tricky but manageable using a back stitch for strength.

The photo below shows the back of the stays after both side seams were sewn into place.

And finally a photo of the stays ready to go for the fitting. I decided to use a spiral lacing for two reasons. It was the most common method of lacing stays in the Seventeenth Century and it seems to be an easier way to do up front lacing stays on your own. The double cross method always feels like it has lace-ends going in all directions!

The shoulder straps and ties are not completed yet so that the correct shoulder measurements can be taken. And that’s it all ready for the fitting.

In a future post, I will describe the fitting process and the show the final stays, with kind permission of the new owner.